Forthcoming in: HBR Chinese, February 2020

Silicon Valley, already used to a deteriorating news cycle, had a particularly tough run this year. The antitrust allegations against Facebook and its fellow FANG companies are gaining momentum; Uber had a traumatic IPO, not only because its Wall Street debut delivered the largest loss a company ever suffered on opening day but because worker protests spoiled the party; and WeWork, which tried to boldly assert valuation prominence by announcing a $47 billion valuation, short after saw its IPO fall into chaos and its CEO fall in disgrace.

Facebook, Uber, WeWork are pioneers of technology’s recent golden age which started in the early 2000s and accelerated through the years of the global economic crisis, leaving no sector untouched. But it wasn’t merely maturing technologies which fuelled this “Fourth Industrial Revolution”. Other important factors were the availability of cheap money, a growing middle class in emerging markets and a favourable regulatory environment.

Now the tide is turning. Economies entered a new cycle where monetary policy could lose its punch, trade tensions are stifling markets, and regulatory regimes are scrutinized. People and policy-makers are starting to take a harder look at the world’s tech behemoths and wonder: is this scale? Or is this “scalure”? Will the shooting stars keep rising or crack under their weight?

The Fourth Industrial Revolution is coming off age. But the beginning backlash against tech is not just about putting the Silicon Valley pioneers back in their place; it is about giving birth to new leadership paradigms, enterprise architectures and technological solutions which aim to make companies more responsive, inclusive and driven by purpose.

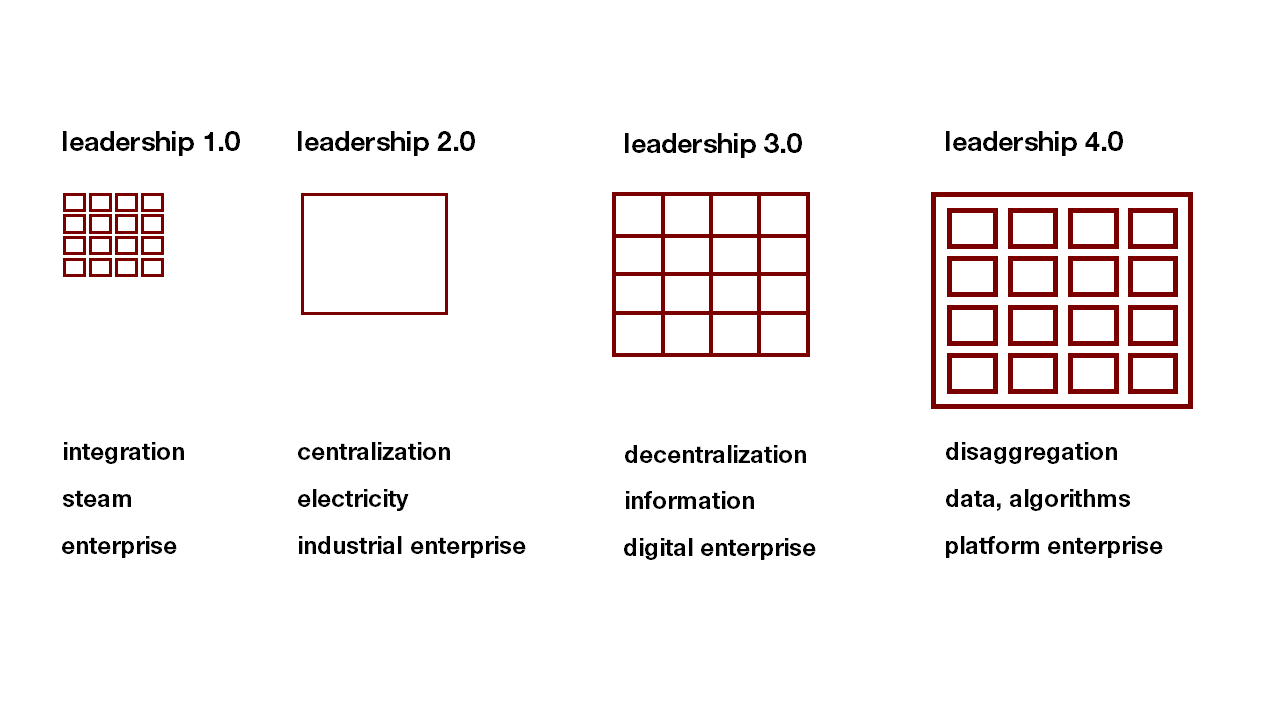

For most of modern economic history, processes of production and distribution were carried out by small personally owned and managed firms. Call this Leadership 1.0. This changed dramatically with the rise of fossil fuels. Manufacturing processes became more sophisticated but more complex, too; industries that centralized processes in a single factory saw their output soaring as transaction costs dropped and energy got used more intensively. The visible hand of managers started to supplant the invisible hand of the market. Call this Leadership 2.0.

Leadership 2.0

In the United States, the shift toward Leadership 2.0 accelerated at the turn of the twentieth century – a period which holds big lessons for those occupying the commanding heights today. After the first great merger movement from 1885 to 1905, a few dozen industrial trusts had replaced thousands of small firms. Only two decades later, half had gone or fallen behind.

One reason was electrification. The trusts were powerful and rich; they even were fast to implement electricity; but most got stuck in old ways of manufacturing. Electricity was not just about replacing steam; it was about redesigning the plant. Those who saw the difference became more refined and efficient by moving away from the centralized power stations of the steam age and attaching small engines where needed, from conveyor belts to overhead cranes.

But electricity was not the only fork in the road. With the first great merger movement, America’s big railway companies, energy firms and manufacturing pioneers decayed in public perception from epitomes of modernity to enemies of society. Senator John Sherman wrote in 1890, “If we will not endure a king as a political power we should not endure a king over the production, transportation, and sale of any of the necessaries of life.” The growing disapproval of the trusts gave rise to a new political agenda: the progressivism of the early 20th century.

The Sherman Act still constitutes the core of American anti-trust law. Its creation is a cautionary tale about scale quickly turning to scalure when companies squander their social license to operate. The electricity story, on the other hand, feeds the myth of capitalism as a system which is not about the big beating the small but the fast beating the slow – an insight sometimes mistaken for the idea that size doesn’t matter. The trusts which survived the carnage (such as GM) became even bigger and so did the “electric natives” which stepped out of the shadow.

Leadership 3.0

If 2.0 was all about the “managerial revolution” and the rise of the multiunit enterprise, 3.0 became all about its global scale. Globalization became possible not only thanks to a massive political shift in the early 90s but also new information, communication and transportation technologies. The end of the Cold War not only fuelled the expansion of markets but also that of corporate bureaucracies to reap economies of scale on a planetary level. Most of today’s manufactured exports are unfinished goods moving around in global supply chains.

Like electricity, information technology was not just a component innovation; it allowed enterprises to bring larger portions of their supply chains under control whilst compensating for higher degrees of complexity with decentralized command and control structures: in the 1960s the often-dreaded matrix organization was born in the aerospace industry. In the 1970s, McKinsey created its famous 7S framework which emphasised coordination over rigid hierarchies. Leadership 3.0 was first about usurping the market – and then replicating it on the inside.

If leadership 3.0 was all about enabling enterprises to go global, leadership in the Fourth Industrial Revolution became about helping enterprises expand into cyberspace, a new sovereign space long seen as fundamentally distinct from the sort of spaces states controlled. “The internet is the largest experiment involving anarchy in history”, Eric Schmidt wrote only five years ago.

Leadership 4.0

The past two centuries saw more transactions moving from the market to the firm. Leadership 4.0, however, seems headed into the opposite direction: it brings back the market. “The last period of globalization was led by 60,000 multinationals; the next period could be led by millions of SMEs”, Jack Ma, the founder and former Chairman of Alibaba told Davos attendees.

But the market Jack Ma is thinking of has little in common with that in the era of Adam Smith; our ability to store, process and analyse massive amounts of information made markets data-rich. And, as these capacities are provided by companies like Amazon, Google, Facebook or Alibaba, it is mostly enterprises that set the rules and extract the returns.

The consequences are huge, not only for how enterprises interact with consumers but also for how they organize themselves: the chief rationale for large corporate bureaucracies – the old mantra that carrying out a transaction inside the company is cheaper than outside – is vanishing as data-powered platforms lower the costs of contracting, resourcing and managing all kinds of processes traditional markets weren’t able to handle before.

If the leadership transition to 3.0 was all about decentralization; the transition into Leadership 4.0 is thus about disaggregation. Earlier leadership paradigms were about organizing business; Leadership 4.0 is about the business of organizing via sensors, data and algorithms. When to become a platform and when to join one is today’s most pertinent strategic choice.

The result is an era of opposites, manifest in unprecedented corporate bigness, epitomized by Apple and Amazon which became the first privately owned trillion-dollar companies and, on the other side, in long-gone smallness, epitomized by the gig-worker as the quintessential one-man firm enabled by data and machine learning platforms.

Like in the days of the old industrial trusts, the maturing of a new architectural paradigm will create winners and losers. Firms like Facebook, Uber and WeWork are pioneering the Fourth Industrial Revolution — will they also be remembered as pioneers of leadership 4.0? Similar to the early 20th century, the answer won’t just be about technology. It will be about trust.

Technology enables scale but trust is what’s needed to achieve and maintain scale. Amazon’s ability to sell us connected devices that record everything we say in our most intimate environments is not just a technological achievement, it is a trust achievement. Corporations are more than a nexus of contracts; they are a nexus of relations built on trust.

But surveys show that trust in business is sinking, not because of an economic crisis but because of a feeling that those who are in power are getting away with murder. Many companies topping todays’ Fortune 500 list long topped the list of the most loved firms as well. But this has now changed. From Google’s sexual harassment cases to a popular outrage over municipalities competing for Amazons HQ with generous subsidies, to reports over Facebook’s obliviousness to its platform’s manipulative possibilities, trust by default is gone.

Technology firms can no longer count on just mesmerizing us with the Faustian bargain of free tools for free personal data. If big data and smart algorithms are the new oil, trust is the operating license to drill. And, obtaining trust is harder than ever. Leadership must move from trust by default to trust by design, from reaping trust to seeding trust. But how?

First, leadership 4.0 is about scaling trust through responsiveness. Organisms always had to adapt to survive in fast changing environments but stakes grow with complexity and scale. As the economist E.F. Schumacher argued in Small is Beautiful: “the greatest danger invariably arises from the ruthless application, on a vast scale, of partial knowledge”.

Just over the past weeks, we experienced another freak accident with a Tesla, a Google outage that locked people out from their homes and deactivated their baby monitors, as well as alarming reports on the declining security of high-tech planes. The spectre of large-scale accidents is compounded by fears over deliberate interruptions through espionage or sabotage.

In 2014, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg proclaimed that his company’s motto would change from the iconic “move fast and break things” to “move fast with stable infra”. Building trust means investing in maintenance and repair. In 2016, Facebook learned the hard way that this also applies to content. Facebook’s expanding army of content moderators already exceeds the entire workforce of Twitter which just announced its own strategy to keep its platform clean.

Moreover, the organizational mash-ups that result from organizations both acting as platforms and forming part of others makes it impossible to master the new complexities of the Fourth Industrial Revolution within one organization. The Google cloud blackout hit thousands of users who were not even aware of using Google services. In a platform economy, responsiveness is a team sport, forcing all stakeholders to form new partnerships and practices.

Second, Leadership 4.0 is about scaling trust through inclusivity. Data is the new oil but all of us, the hundreds of millions who are passively or actively producing the data, are often poorly rewarded. A slew of technology start-ups is now aiming to tackle this challenge by rethinking platform ownership and data ownership from the ground up.

The Israeli ride-hailing platform La’Zooz aims to differentiate itself from companies like Uber or Lyft by operating like a digital cooperative, allowing both drivers and clients to partake in the success of the business. Platform cooperatives are still small but hold the promise of making poorly paid jobs from chauffeuring to housekeeping more fairly paid.

Other efforts focus on data-ownership. In 2016, Jennifer Lyn Morone made headlines by registering herself as a company in Delaware to monetize her personal data. What started as a form of protest by the American artist turned into the start-up DOME, or database of me, which helps people collect and store personal data to trade it on their own terms. Start-ups like DOME, CitizenMe or Datacoup are still small but touched a nerve.

It is of course uncertain how scalable these avant-gardist ownership structures really are but unless the pioneers of the Fourth Industrial Revolution become more inclusive, consumers will turn away and regulators will move in. Europe led the way with its General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) which was designed to give users better control over their personal data and is binding for every organization doing business in Europe.

Third, leadership 4.0 is about scaling trust through doubling down on purpose. “The motivation of man is not… the pursuit of happiness or utility but the creation… of worthwhile endeavours”, Colin Mayer argues in his visionary manifesto Prosperity. The Oxford professor finds that consumers and employees are asking more often a simple question: scaling for what?

Scale comes with big risks but even bigger rewards if what it unlocks is of urgency. Now, what if that is not the case? What if the company must not only manufacture the good itself but the desire for it as well? The case for scale suddenly feels less compelling. Doing something useless or harmful more efficiently doesn’t make it better – it makes it worse.

Silicon Valley had a bad run lately – with a notable exception: its single most successful IPO this year – even after a stark stock market price correction over the past months – was Beyond Meat, a company that seeks to scale artificial meat and transform the way we consume proteins. Beyond Meat is not just a great business; it is a purpose worth pursuing; worthier for sure than scaling factory farming for greater efficiency.

Leadership 4.0 means moving from trust by default to trust by design. In the face of climate change, mass extinctions, biodiversity loss and rising societal tensions, trust by design is no longer just about scaling smarter; it is about being smarter about what to scale.